Cochineal and Carmine – Cost-Effective Natural Colours

The Story of Cochineal

For food and beverage manufacturers, it is normal to pay special attention to innovations and the latest industry changes. In regards to natural food colouring solutions, marine or algae-based formulations and technology advances in purification might come to mind. Yet it can be important, even strategic, to look back at colours that have been around since ancient civilizations. The story of cochineal and carmine dates back to antiquity for a reason. The crimson red natural colour’s longevity is an indicator of its overall effectiveness. Colour from cochineal extract and carmine has been used for centuries, dating back to the 15th century. Here are some fast facts on the centuries-old, sought after natural red:

The story of cochineal and carmine dates back to antiquity for a reason. The crimson red natural colour’s longevity is an indicator of its overall effectiveness. Colour from cochineal extract and carmine has been used for centuries, dating back to the 15th century. Here are some fast facts on the centuries-old, sought after natural red:

- 16th century Spanish kings imported cochineal by the tons for elite clothing and furniture dye. Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, and Walter Raleigh imported the largest haul of cochineal on record at 27 tons carried by three Spanish ships.

- The infamous British wool “Red Coats” were dyed with cochineal in the 17th century by skilled Dutch dyers.

- The history of and widespread use of cochineal is celebrated in a widely attended, traveling art exhibit, The Red That Colored the World.

Behind the Scenes of Cochineal and Carmine Production

Cochineal (Dactylopius coccus) are immobile scale insects native to tropical and subtropical South America, as well as Mexico and Arizona. These insects live on the pads of prickly pear cacti, feeding on the plant’s moisture and nutrients. Cochineal can damage and potentially kill their host cacti by draining all of its resources, and if they are not controlled, the insects can spread voraciously in a decidedly pest-like manner. Like any plant, infestations can be very severe. While colour production was not originally designed to prevent infestation, it is one way to responsibly manage the prickly pear crop mortality.

Greenhouse cochineal production is also a good agricultural practice, as it provides a more regulated environment for quality control. The first step in colour production is gently collecting the cochineal from the cacti. The insects are then dried and carminic acid colour is extracted.

Peru is currently the largest producer of cochineal. Chile and Mexico also export cochineal. In Mexico, production and exportation of the natural colour have enabled poverty alleviation and female literacy initiatives.

What’s Old is New Again: A Fresh Look at Carmine and Cochineal

Colour from cochineal is found across a number of industries today including food and beverages, inks, cosmetics, and pet food. The primary colouring component, carminic acid, is available in two different forms:

- Carminic Acid: the water-soluble extract from the cochineal

- Carmine: an aluminium lake of carminic acid

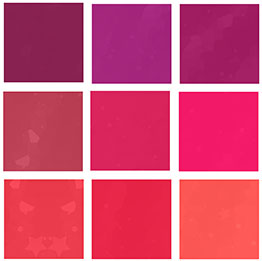

As food colours, carminic acid and carmine are great natural colourants. With excellent heat and light stability, they provide shade options for a wide range of applications, ranging from beautiful pinks and bright reds to oranges and lavenders. Whilst both options are labeled as E120, carminic acid provides an orange shade typically working well in low pH applications, whilst carmine gives a very bright red shade with good light and heat stability, yet with some limitations in acidic food and beverage applications.

From a performance standpoint, colours derived from cochineal are certainly amongst the top natural colour contenders, especially with its cost-in-use advantage. However, there are a couple drawbacks to the colour, but the impact isn’t necessarily applicable to every brand or region. Colour from cochineal is generally not considered Kosher or Halal nor vegetarian or vegan, given its origin. At one point, the insect source of cochineal was under some scrutiny, but lately, insects are an emerging food trend, and the acceptance of insect-based foods is growing. At the Global Food Summit, which ran on the sidelines of the 2018 Winter Olympics, rice cakes and cookies made of edible insects were presented to showcase how traditional cuisine can be combined with emerging food ingredients, according to Mintel. Sensient polled consumers to better understand their feelings about insect-based colour, and a little over 40% indicated insects as a viable source option for natural food colour. Colour from insects could be more accepting over time, as insect-based proteins and ingredients make their way into more mainstream foods.

Another challenge with carmine specifically is its permissibility in certain applications in Europe. In 2014, the EU aluminium regulation limited the conditions and levels of use for aluminium-containing food additives. As a result, it became mandatory to calculate the total aluminium content of the final product to make sure it is in line with regulations. In addition, carmine is not permitted in all food categories, for example, it is not allowed for usage in ice cream.

Lastly, carmine has historically been a natural colour with severe price volatility. The harvesting of cochineal can be greatly impacted by weather and other issues, and there are only a few worldwide growing regions. While carmine is one of the more efficient natural colour sources, the historical price volatility has understandably been a major source of frustration for manufacturers when it comes to forecasting and budgeting.

From a performance standpoint, colours derived from cochineal are certainly amongst the top natural colour contenders, especially with its cost-in-use advantage. However, there are a couple drawbacks to the colour, but the impact isn’t necessarily applicable to every brand or region. Colour from cochineal is generally not considered Kosher or Halal nor vegetarian or vegan, given its origin. At one point, the insect source of cochineal was under some scrutiny, but lately, insects are an emerging food trend, and the acceptance of insect-based foods is growing. At the Global Food Summit, which ran on the sidelines of the 2018 Winter Olympics, rice cakes and cookies made of edible insects were presented to showcase how traditional cuisine can be combined with emerging food ingredients, according to Mintel. Sensient polled consumers to better understand their feelings about insect-based colour, and a little over 40% indicated insects as a viable source option for natural food colour. Colour from insects could be more accepting over time, as insect-based proteins and ingredients make their way into more mainstream foods.

Another challenge with carmine specifically is its permissibility in certain applications in Europe. In 2014, the EU aluminium regulation limited the conditions and levels of use for aluminium-containing food additives. As a result, it became mandatory to calculate the total aluminium content of the final product to make sure it is in line with regulations. In addition, carmine is not permitted in all food categories, for example, it is not allowed for usage in ice cream.

Lastly, carmine has historically been a natural colour with severe price volatility. The harvesting of cochineal can be greatly impacted by weather and other issues, and there are only a few worldwide growing regions. While carmine is one of the more efficient natural colour sources, the historical price volatility has understandably been a major source of frustration for manufacturers when it comes to forecasting and budgeting.

Improving Price Volatility

Our Sensient Food Colors Peru location enables us to participate earlier in the process flow of colour from cochineal, so we can provide cost-effective carmine and cochineal options. We are working with our farmers to establish full traceability down to the individual cochineal plots. Sensient’s Agronomy team equips our partner farmers with the tools necessary to cultivate a steady supply of cochineal at fair market pricing, all while preserving the environment. By creating longer-term partnerships, we can create a more stable price environment for food, beverage, and pet manufacturers. While every natural colour crop brings different challenges to the table, our end goal with all of our vertically integrated colours is the same—more for less! The opportunity to formulate with carmine and cochineal spans vastly across applications, including… With the bright, stable shades available, innovation can be endless and cost-effective with Sensient’s portfolio of vertically integrated cochineal and carmine options.

Interested in sampling our cochineal collection? Request your specific shade here.

With the bright, stable shades available, innovation can be endless and cost-effective with Sensient’s portfolio of vertically integrated cochineal and carmine options.

Interested in sampling our cochineal collection? Request your specific shade here.